by John P. Pratt

13 May 2013

©2013 by John P. Pratt. All rights Reserved.

| 1. Counting |

| 1.1 Inclusive Counting |

| 1.2 Exclusive Counting |

| 1.3 Magic Zero |

| 2. The Week |

| 2.1 Seven-Day Cycle |

| 2.2 Moses and Manna |

| 2.3 Naming Weeks |

| 3. The Uniform Enoch Year |

| 3.1 A way to count weeks |

| 3.2 364-Day Cycle |

| 3.3 Four Similar Quaters |

| 4. Align with Trecena |

| 4.1 Align Holy Days |

| 4.2 Begin at Resurrection of Jesus |

| 4.3 Evil |

| 5. Conclusion |

| 5. Conclusion |

| 3. Conclusion |

| Notes |

After the last article on the Uniform Venus Calendar, it seemed appropriate to re-examine the Uniform Enoch Calendar. That has remained unchanged for many years and has not been questioned. As a detailed study was done durning this last week, analyzing hundreds of historical dates, it became clear that one minor adjustment needs to be made.

The pattern of the calendar remains unchanged, but the starting point needs to be adjusted to begin later by two weeks. Years ago when the choice of starting point was being made, there were two choices. One was picked because of alignments on the Firstfruits holy day. Since then, the similar Uniform Jubilee Calendar has been discovered, and it is now clear that those alignments were for the Jubilee rather than Enoch Calendar. Rather than discuss all the reasons, it appears best just to start from scratch. So if you no nothing about the Enoch calendars, that will work just fine. In fact, I'm planning to write a home school course about sacred calendars, and it is hoped that this paper will be similar to one of the first chapters.

Beginning with this article, work is in progress for a Christian home-school book explaining sacred calendars and how they testify of God, Jesus and the prophets. Sections 1 to 3 of this paper are intended to be rewritten with more examples and explanation for that book. If any readers let their children read those sections and have feedback for me, please let me know. And don't let the pictures of apples fool you, this is tricky stuff and all readers should read those sections. In fact, I'm not aware of any other course that teaches it this way. I'm assuming the reader knows nothing about the subject, with a pure, open mind like a child. Adults might have learned other things and question what it written here. I'm not going to take the time to answer those questions. Just be like a little child, teachable, and hopefully it will make sense. Scholars may not get past my section on counting because they think they already know how to count. I had to relearn from scratch and it wasn't easy to forget what I had learned that was wrong. For example, I had to redraw the picture of Mayan counting below because I've never seen they system presented in the way it was actually used! The later sections are more advanced, assuming the reader is already familiar with some of my work from other articles.

|

When we are counting apples everyone pretty much agrees that the first apple counted is called "one", and the second is "two" and so on. If there has been one King Henry, and another one comes along, the second king with that name is usually called "Henry the Second". Every knows what is meant without a special course in counting.

The problem in counting arises mostly with counting time. Sometimes it is desired to start counting time from some event, without changing the units of time. For example, when the United States was born on 4 July 1776, people wanted to number the years of the country's independence. What year should they count as "Year 1"?

Let's ask the question right down to the day. You were born at some time of day on your birthday. What would you call "day 1" of your life? Would it be your birthday? What if you were born at one minute before midnight. Would you still count the whole day as day one? And when would you say that you were "one day old"? Stop and think about this before reading on. It is a fundamental question for calendars. How would you set up a United States Calendar to begin counting?

The answer chosen for the United States is the same as is often done for kings. They counted 1776 as year 1, with 1777 as year 2, and so on. This counting is used in official documents, such as when the U.S. Constitution was adopted in 1787, called the twelfth year of the "Independence of the United States".[2] Notice that when using this method, one cannot simply subtract 1776 from 1787 to get 12. That doesn't work because 1776 was "included" in the count. But it does work to subtract 1775 (which is rather like the 0 year of independence) from 1787 to get 12.

This way of setting up a calendar is called "inclusive counting". With inclusive counting, the time unit in which the event happened is "included" and counted as "one", or the "first". Inclusive counting would say that the day you were born is your first day of life, even if you only lived one minute of it. In counting years of a king, inclusive counting would say the first year of a king is the year in which he began to reign.

In the Bible, after the Exodus of the children of Israel from Egypt, they began to count time from that event. They used this same inclusive method used by the United States. The year in which the Exodus occurred was called the first year of the Exodus. The very next New Year's Day began the second year of the Exodus (Exo. 40:17). That is very important to understand when one reads that the temple of King Solomon was begun in the 480th year of the Exodus (1 Kings 6:1). That is, it is important if you really care to know exactly what year is meant.

One place inclusive counting is used is in naming the centuries since Christ. The very first 100 years after his birth are called the "First Century". That makes sense, doesn't it? But then there is a confusing problem. The years in the 100's were in the Second Century, the 200's in the Third Century, and so on. We are now in the years of the 2000's, and it is called the "Twenty-First Century". We count centuries inclusively, but it can be confusing because one expects the 2000's to be the Twentieth Century, but that is not how centuries are counted.

This has been the problem with counting the three days until Jesus resurrection. The Jews at the time of Jesus always counted time inclusively. On the Easter Sunday on which Jesus resurrected, He walked with two men who did not recognize him. They told Him that Jesus had been crucified and that today was the third day since then (Luke 24:20-21). He was crucified on a Friday and they counted that as the first day. Saturday was the second and Sunday was the third day after Friday. No one had to ask, "Wait a minute, just how are you counting?" It was as simple as one, two, three!

But that isn't the only way to look at it. Now let's look another way of counting days.

|

Some nations counted the reigns of kings exclusively. They called the year the king was crowned as the "ascension year" because that is the year he ascended to the throne. The next year was called the first year of his reign. This made the math come out better, because in the second year of reign he would have been king for 2 years, not one year. If the U.S. had done this, then 1777 would have been year 1, and 1787 would have been year 11, being 11 years after 1776. They could also call the ascension year the last year of the former king. The year 1776 would have called the last year of King George. That doesn't sound as great, but it sure helps with the math. The main point is that there are at least two ways to do it and both have been used in history.

Just for the record, there is a third way. One could "round off" the years and say that if the king reigned over half a year to call it the first year, but otherwise call the next year the first. This is often done in listing how many years a king reigned. In the Bible, when it says that a man lived 70 years, it looks like those years were rounded off to the nearest whole year.

|

This brings us back to counting because the ascension year is like a "zero" year. Some people invented something wonderful, almost magic, called a "zero". If you have learned Roman numerals (which you should), you might have noticed they did not have a zero. That made it really hard to do even simple arithmetic. Try multiplying a couple of numbers and you'll see. It is our "zero" that makes it simple for us.

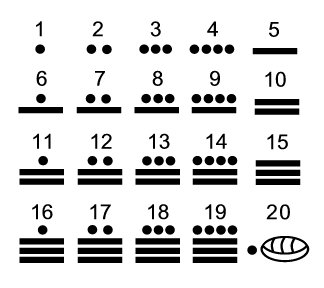

What is a zero? There are at least two uses. The first use of zero is to mean "completion". Here's how it works. Our counting system is based on the number 10. We have nine different symbols we use to count from 1 to 9 as shown on the apples in Figure 1. When we get to the next apple, instead of making up a tenth symbol, we use a "zero" which is really just a place holder. We put it after a "one" to mean "one complete bundle of ten". The number "ten" is actually all contained in the number "1". The zero only means "complete bundle of ten". Think about that until it sinks in. That is the magic! Then to count the next apple, we replace the placeholder zero with a real number "1" in that place, so we have one more than a set of ten, or eleven. (See Figure 2.) The next place over will be for ten sets of ten or one hundred. We are all set up to count a high as we can.

To make sure you see it, think of the apples in boxes. If a box holds ten apples, then the "0" means the box is full, or complete, and the "1" tells you how many boxes. Figure 3 shows two boxes of ten apples. We say there are "20" apples all together, where the "2" means two sets of ten, and the "0" means both sets are complete. The zero is different from the other nine numbers because it was not meant to count "zero apples", which might not even make sense. We'll talk more about how the zeroth apple might actually make sense.

|

Now for another use of zero. Zero can be thought of as the number before "1". In some ways it does not make sense to talk about zero apples. If I'm going to have zero apples, I might as well think big and have zero ships or zero airplanes. Nothing is still nothing.

|

That idea works for numbers other than ten. If you are putting a dozen apples in each box, then what is the "zero" for a box? Look at Figure 5. That's right, the "zero" of the dozen in the second box is the number 12 of the first box.

|

It is this second use of zero, as being the number preceding "1" that is of concern in calendar work. The part about completion was discussed mainly because it is so little known. Now that we up to speed in counting, let's start by counting by sevens.

We are all familiar with the week of seven days. The week is a simple day count that just keeps counting by sevens over and over. So why did we have to do all that learning about counting? What could be hard about a week of seven days? You might be surprised. There may be many things about the week that you probably haven't thought of.

For example, have you ever realized that the week can be thought of separately from the rest of the calendar which counts months and years? That is, someone can count months and years entirely differently from us, and yet still count the seven days of the week. In fact there are many calendars which count months and years differently but they still count days by sevens because of their religion.

An example of this is that a few hundred years ago a mistake was found in our counting years. To fix it, ten days were removed from October, 1582. That changed that month and year, but the week was not interrupted at all. It just kept counting by sevens as if nothing had happened. There had been no mistake in the week.

|

Look again at Figure 7. Notice that the Sundays are shown in red. Why? That is because this calendar is for Christians, who believe that the first day of the week is holy because that is the day on which Jesus overcame death by resurrecting. In a way we are celebrating Easter Sunday every week just by worshipping on that day! Before that, the Lord's people worshipped on the seventh day, which we call Saturday. That was because the Lord told Moses that he created the earth in seven days and rested on the seventh, and so should his followers. But at the resurrection of Christ the day of worship for his followers changed to be the first day of the week. That was the day on which the met to keep the sacrament of the Lord's Supper, which they called "breaking break" (Acts 20:7).

Have you thought much about the names of the days of the week? The names we use came from assigning each day to a planet, thinking of both the Sun and Moon as planets. That idea did not come from Christianity. There was a Catholic pope a thousand years ago that decided to ask everyone to change the names of the week to something more Christian. He suggested the days something verymuch like "Lord's Day", "Second Day", "Third Day", "Fourth Day", "Fifth Day", "Sixth Day", and "Sabbath". But the people thought that was too much to ask. Only the country of Portugal agreed, so they use those names to this day, as does Brazil (a Portguese country). It is very hard to get people to change their ways.

So how accurate has the 7-day count been? That is, has anyone goofed up the count? Is the day Sunday on our calendar the same as Sunday back at the time of Jesus?

There are two answers to that question and they both agree. One is that about six hundred years before Jesus, the Lord's people had forgotten to be careful about keeping the sabbath (seventh day) and the Lord punished them for seventy years because of it. They (the Jews) learned their lesson and have been very careful since never to miss a day. In all of my research, there is no evidence that since those seventy years passed, that even one day has ever been miscounted. We can thank them for that and then the Christians afterward.

The second answer is that in modern times the Lord confirmed two things and implied a third: 1) that Sunday is the correct day to worship, 2) that He calls it "the Lord's day" (the rejected name), and 3) if our Sunday is indeed the correct day to worship, it supports the idea that Sunday has not changed over the years. On Sunday, 7 Aug 1831, He said to the Prophet Joseph Smith:

"For verily this is a day appointed unto you to rest from your labors, and to pay thy devotions unto the Most High; ... remember that on this, the Lord's day, thou shalt offer thine oblations and thy sacraments unto the Most High, confessing thy sins unto thy brethren, and before the Lord", (D&C 59:10).

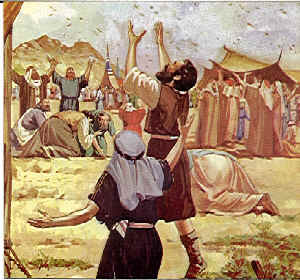

When did counting weeks of seven days and keeping the sabbath (seventh) day begin? We probably all know that the fourth of the Ten Commandments is "Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy" (Exo. 20:8). But how long before that did men know about resting on the seventh day?

To the best of my knowledge, the answer according to what is recorded in the Bible turns out to be only three weeks before the Ten Commandments were given!

There is no record in all of the book of Genesis that any of the patriarchs before the Great Deluge, or even up to Abraham, Isaac and Jacob, kept a sabbath day. They might well have done that, but it just didn't get put into the Bible.

|

If weeks continue indefinitely, is there a way to refer to a specific week? Is there a way of counting weeks? Or is there a way of naming them? Or both?

The answers are yes, yes, yes, yes. Here is where this article start to go beyond what most people have thought about.

There is a set of twenty-four names for weeks provided in the Bible. They also go on continuously. It forms a calendar of 24 weeks long, which just keeps repeating. Almost no one thinks of it as a calendar, but it is because it is a way of counting days and weeks.

The 24 names are the names of 24 priests whose family member presided at the temple in Jerusalem each for one week (see 1 Chron. x:x). They kept taking turns in the same order as long as the temple was in operation. The 24 names each can be translated to English, and each seems to describe the Savior, or something about His life. That rotation of priests forms a calendar, and their names become names for the weeks. We are told in several places exactly when the cycle began and a few well known dates from history when a certain family was ministering.[3]

Now we come to one of the reasons we talked so much about the zeroth day of a set of days. In many of the Lord's calendars, a set of days is apparently named for the zeroth day of the cycle. That is apparently the case for the names of the weeks.

So here is your quiz question: What is the zeroth day of the week?

That's right, it is the day preceding the first day. It is Saturday, the last (seventh) day of the week. The priests began their week of service not on Sunday, but at noon on Saturday. That is when their name began to be applied to that week. The naming can be thought of as being on the zeroth day day of the week. We'll see that pattern three times in this one article. The Mayans used a similar method, naming units for the last day rather than the zeroth, but the Aztecs named units for the first day instead.